My name is Eric, and I’m a nerd. My nerdiness is vast, but I would like to believe its most useful manifestation is in the area of pedagogy. When it comes to teaching, the question that is constantly in the back of my mind is some version of, “Is there a better way to do this?” And the answer, invariably, is something like, “Yes, yes there is. There is an infinitely better way to do this, but it is going to devour most of your mental and physical energy for the foreseeable future.” To which I frequently reply, “Sounds great!”

Over the course of the past decade, I have become convinced that Thinking Maps, in all of their various forms, are the most effective way to improve my instruction across all areas of the curriculum. Here, in my first post, I lay out several reasons the use of Thinking Maps should be considered foundational to your planning and teaching.

Metacognitive Purpose

According to the book Better Learning Through Structured Teaching, there are three domains in which teachers can establish a purpose for a lesson: content (subject matter), language (key terms), and social (SEL skills). To these, I would add a fourth domain: metacognitive. I strongly believe that if we want to develop our students into intellectually autonomous thinkers and learners, we need to teach them to reflect on their thinking and learning. Without a solid familiarity with the structures of cognition, students are unlikely to notice or comprehend what their brains are doing.

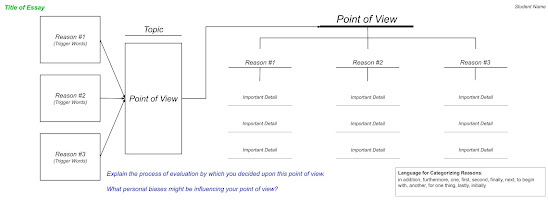

Thinking maps allow teachers to seamlessly build these structures of cognition into lessons on a consistent basis by providing logical, easily recognizable frameworks for thinking. The content purpose of a lesson might be to teach students to provide reasons for their points of view, but a Left-Sided Partial Multi-Flow Map helps them to see the causal relationship between reasons and opinions, satisfying a metacognitive goal as well. An accompanying Tree Map makes clear that reasons need to be clarified and/or elaborated. A bank of words embedded in the map reminds students there is a set of terms associated with this type of thinking, and a well placed Blue Frame of Reference question (more on this in my next post), at the bottom of the map, can remind students to consider their biases when formulating an opinion and/or make a connection between opinion writing and the “Evaluate” level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Making Thinking Visible

I have determined that there are two main categories of Thinking Maps. The first is the student-generated map with which you are most likely familiar. This is the sort of map you ask students to create in order to plan a piece of writing or show their understanding of a particular lesson. The beauty of this sort of map is that it can show the teacher exactly what a student was thinking and how well they understood the task. A quick glance at a student-generated map usually allows a teacher to discern whether a student is on the right track. Did they put adjectives and adjective phrases in the bubbles on a Bubble Map or similarities in the central bubbles of a Double Bubble Map?

The second category of map is what I refer to as a “response map.” This kind of map permits me to show students what I am thinking. An example of this is a “Backstory Tree Map” I created for Literature Circles. As it happens, there are five techniques with which an author can provide backstory in a narrative. I made a Tree Map with five “branches,” one for each technique, and wrote hints on how to identify each technique on the lines below (on a digital version that could be written over or printed as directions). It was then up to the students to identify instances of backstory in their Literature Circle books and classify them appropriately on their Tree Maps. This map achieved the content purpose of helping students learn the five backstory techniques, but it also drove home the metacognitive point that the techniques should be considered distinct categories.

Rigor

The best argument for making Thinking Maps integral to your instruction is the control they give you over the rigor of a lesson/assignment. You can easily build as much or as little scaffolding into a map as you deem necessary.

One way you can do this is by raising or lowering the level of strategic thinking through your map selection. For example, I use three different maps for making text-to-self connections. The first, a Circle Map with a Frame of Reference, allows a student to connect any character in a story to any person in their life. Each connection can be about a different character and/or person, so it is very open-ended. The second map, a Double Bubble Map with only similarity bubbles, forces the student to make much deeper and more numerous connections since they have to choose one character and compare her/him to just one person in their life. The most rigorous text-to-self connections map I have created is actually a series of Bridge Maps which requires the student to make analogical connections, indirect connections which need to be explained in detail. With these three maps at my disposal, the same reading strategy can be practiced with significantly different levels of rigor.

In addition to map selection, you can adjust the rigor of an assignment by embedding more or less scaffolding in the boxes or bubbles of the map (see the above example of the Backstory Map).

Questions from the Metacognitive Frames of Reference are another way to raise rigor, but, since they will be the subject of my next blog post, I will refrain from discussing them until then. For now, I strongly suggest experimenting with using Thinking Maps as often as possible. I think you will find your comfort level will quickly improve. Hopefully, you will have a lot of questions for me in the comment section below!

Writing Every Day,

Eric Lovein

PS: Check out my post about Summarizing Flow Maps!: https://spotlightclassrooms.blogspot.com/2022/03/thinking-maps-for-fictional-narrative.html

...and my video on Circle Maps!:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuQ9RkXXZcI