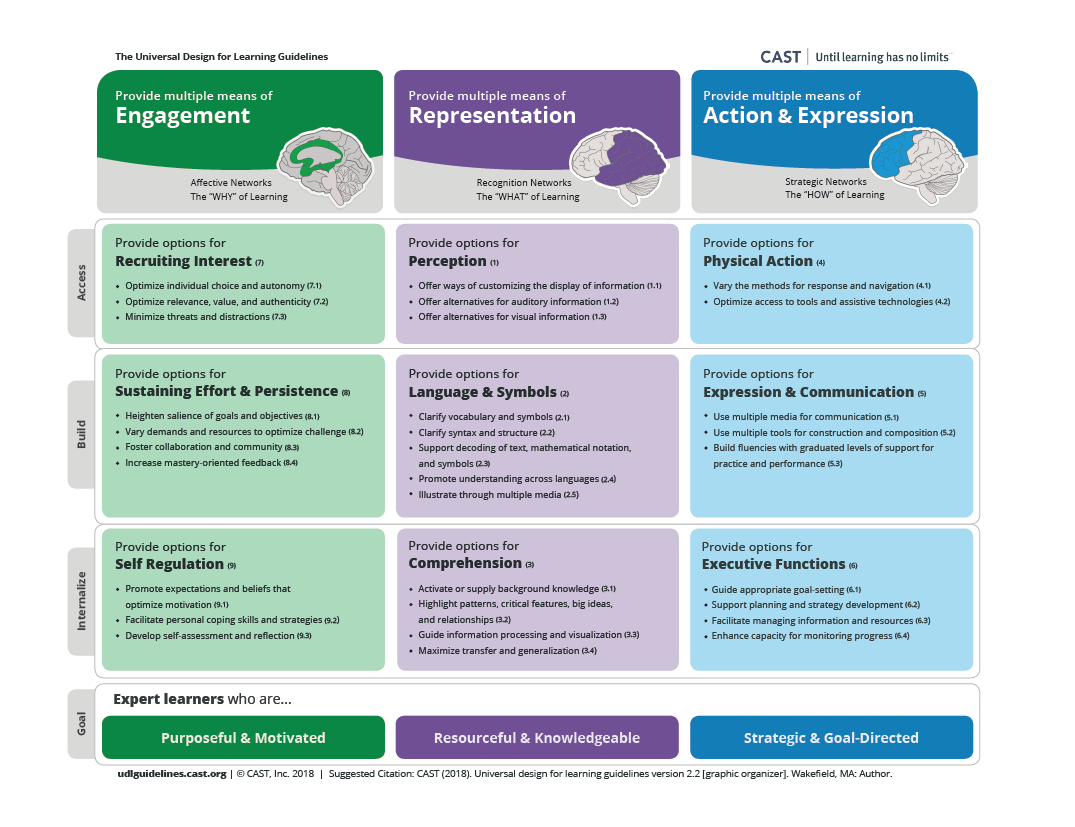

You can think of UDL as comprehensive differentiation that meets the needs of all students in three core areas: Engagement, Representation, and Action & Expression. As you can see in the graphic below, Engagement is the “Why?” of student learning; here we are concerned with motivation, affect, agency, interest and SEL skills. Representation involves what methods and materials are being used for and by the student to learn the required content; if the objective is for the student to learn how to add mixed numbers using the standard algorithm, the means (or path) to this objective can be varied (realia, videos, white boards, etc.). Finally, Action & Expression concerns the assessment of the student’s learning. If the objective is for the student to demonstrate knowledge of the causes of the American Revolution, the way they demonstrate this knowledge (the product) can be varied (presentation, video, essay, skit, test, news article, etc.).

Obviously, designing your classroom learning environment and lessons to accommodate the unique needs of each student sounds like a daunting task, and I will not try to make an argument to the contrary. I will, however, propose a method for slowly rolling out UDL in your classroom over a series of years, which I hope you will find logical and reasonable. For a variety of reasons, I feel it makes sense to, initially, only tackle one of the aforementioned core areas each year, beginning with engagement in year one.

This UDL Progression Rubric is designed to help teachers monitor their own progress towards “Expert Practice” and is a great way to get a clear picture of what a well-designed UDL classroom could look like. My fear is that a skeptical teacher could read through the various descriptions of how students would operate in such a classroom and determine that “we just don’t have the kinds of kids who can do these things.” Initially, I shared this concern, but I soon realized that, if our kids lack the skills and competencies to be UDL students, then teaching them these skills and competencies should be job one. I began referring to the prerequisites they would need as a “meta-curriculum.” In other words, to as great an extent as possible, I should try to weave them into everything I do all day.

It is clear that the architects of UDL view Engagement as the first, crucial step towards UDL success. This makes perfect sense, given that students who feel they are in a safe, welcoming environment in which their own interests and abilities are taken into consideration are much more likely to be ready and motivated to learn. In my view, a teacher who is reaching “Expert Practice” levels in Engagement has already gone a long way towards preparing students to be successful in the areas of Representation and Action & Expression. In the rest of this post, I will describe what I perceive to be the ideal UDL student and classroom environment and lay out some strategies I have begun to use with my own students to set them up for success. Future blog posts will explore these strategies in deeper detail.

In the “Recruiting Interest” section of the Engagement progression rubric, you will see terms like “make choices or suggest alternatives,” “authentic,” “self-monitor and reflect,” and “self-advocate.” All of these terms paint a picture of a student who is confident, assertive, motivated, and self-aware in terms of both their personal interests and social-emotional needs. One of Dr. Hammond’s goals involves increasing students’ self-efficacy, which dovetails perfectly with the above description. Of course, a student who is designing their own projects and assignments and monitoring their learning environment for distractions and threats is taking a great deal of ownership of their learning and likely experiencing a strong sense of agency.

The “Sustaining Effort and Persistence” section talks about students creating their own personal goals, selecting their own content and assessments, and collaborating “to add to the multiple options offered to challenge themselves and identify appropriate resources that connect to their interests and passions.” These goals imply a similar need for the skills and competencies mentioned above. Additionally, the teacher is expected to, “Create a classroom culture where students work together to define goals, create strategies, provide feedback to each other and push each other with mastery-oriented feedback while building integrative thinking,” and empower students, “to use mastery-oriented feedback independently to self-reflect, self-direct, and pursue personal growth in areas of challenge.” When I first read these descriptions (along with those in the Recruiting Interest section), I realized that all five of the SEL competencies (Self-Awareness, Self-Management, Social-Awareness, Relationship Skills, and Responsible Decision-Making) were going to be crucial to cultivating such classroom cultures and students.

Speaking of SEL skills, the third and final section of the area of Engagement is called “Self-Regulation,” which is just another term for self-management, but this area requires even more than that. Here, students are expected to be willing and able to support their, “own self-talk and support one another's positive attitudes toward learning.” These goals require both self-efficacy and relationship skills. Further, students should, “self-reflect, accurately interpret their feelings, and use appropriate coping strategies and skills to foster learning for themselves and their classmates.” SEL, SEL, SEL.

It is an oversimplification to say that the Engagement portion of the UDL is simply SEL by another name. While SEL skills clearly play a major role, there is also a strong academic bent to this area which includes a student’s ability to identify their own preferred learning styles, settings, strengths, weaknesses, and interests. In addition, the student should be able to create their own learning plans, self-assessments, rubrics, and projects. There is also a collaborative aspect to Engagement, which clearly benefits from social awareness and relationship skills but also requires the ability to have academic discussions.

This year, I have tasked myself with experimenting with various ideas for improving my classroom Engagement. So far, these ideas have included making my classroom a more relaxing and enjoyable place to learn and teaching my students to engage in casual conversations. I have also tied Engagement to my ELA instruction by giving my kids regular opportunities to reflect on their SEL competencies and academic skills through journaling and Kagan structures, reading novels and Wonders stories that address SEL skills, and writing personal narratives that involve their experiences with the aforementioned competencies and skills. Over the course of the next few months, I will delve deeper into each of these areas and report on any future ideas with which I begin experimenting.

Writing Every Day,

Eric Lovein